From Cairo, you go down to Alexandria, or up to Aswan. In Egypt, up is south and down is north: that is how the River Nile flows. This was not hard for me to get used to as Upper Canada and le Bas-Canada were similarly named according to the flow of the St. Lawrence. Encore aujourd’hui, de Montréal on descend à Québec.

I asked around at school about going to Alexandria. “Oh, you mean Alex,” somebody said.

Only the rickety mini-buses and shared taxis leaving from the unpaved lots under the bridge near the Hilton Ramses still go to Iskandaria. All the kids at the American University call Alexandria “Alex”. Saying Alex is to them what acronyms are to the NGO business and vogue-words are to management consultants. “Alex” is Egypt sanitized, simplified and westernized, just the way they like it.

On a recent weekend I took a trip down from Cairo to Alexandria. We took the French train, which is very slow. The Egyptians chose to call their worst train the French train, and their best train the Spanish train, for reasons that are left to the traveler’s imagination. There is no English train, but there is one called TurboTrain. Apart from SuperJet, the buses generally are not named.

Alexandria’s Eastern harbour is protected from the sea by a narrow peninsula that juts out exactly West to East. On the west tip of the peninsula is a citadel named Fort Qaitbey. The citadel was meant as a human complement to the peninsula. The one guards the harbour from invaders, and the other from the waves.

We walked out onto the peninsula to see the citadel. I imagine, although I can’t be certain, that the prevailing winds are northerly there. On that day, at least, there was a strong northerly wind. The Peninsula was being battered, but holding. The fort stood tall and looked not worse for wear, though in reality it had failed long ago. A felucca – let alone a tank or a plane – is sufficient to circumvent it.

If you look closely though, there are signs that the peninsula is failing too. The north side has had to be built up with big blocks of concrete. They are poured with loops of rebar imbedded in them so that a crane can lift them into place.

One day no one will come to put more blocks where the others no longer stand. The citadel will join Cleopatra’s palace, the Great Library and the Lighthouse, at the bottom of the sea: Another fallen Ozymandias in an antique land.

It’s like Blackjack: The player’s only got one advantage, and that’s deciding when to quit. In the long run, the House always wins. The waves are the House in a game we can’t get up and walk away from, and no matter how good our run, the waves will flatten us with patience.

All along the shoreline, on the blocks of concrete, are men fishing. I was speaking in French with Elizabeth and one of the fishermen overheard us and came over. Apparently he had understood some of what we were saying, or at least recognized the language (Many people don’t recognize the Canadian French – just today an American girl at school asked “Are you speaking Argentinian?”).

All along the shoreline, on the blocks of concrete, are men fishing. I was speaking in French with Elizabeth and one of the fishermen overheard us and came over. Apparently he had understood some of what we were saying, or at least recognized the language (Many people don’t recognize the Canadian French – just today an American girl at school asked “Are you speaking Argentinian?”).The fisherman spoke to us in French. I imagined he was dredging up the remnants of grammar school drills. Today, not many Egyptians learn French. It is interesting, however, to see how French has percolated into Egyptian Arabic. Gournal is a newspaper (Journal – J is pronounced G in Egyptian Arabic); kanaba is couch (canapé); dush is shower (douche), mersi is thank you, and so on.

The commonalities between Spanish and Arabic are also interesting. The indefinite article el or al is the same, as are some words. Zeit Zaytoon is Olive oil (aceite de aceituna, at least in Latin America) for example.

One potential parallel I have recently come across is between the Arabic verb ‘and and the Spanish andar. Andar is a flexible word and I never completely understood it, even after my time in Chile. The meaning in Arabic is close to the “to be” sense of andar in Spanish (e.g. Silvia hoy anda por los 23 años). When the Arabic verb was explained to me I felt as though I suddenly understood a branch of the Spanish verb that had been troubling me. Perhaps the original meaning of andar (walk) in Spanish was fused with the Arabic homophone producing the wide range of meaning of the verb in modern Spanish usage.

There are other such oblique parallels. For example a frying pan is sometimes called sarten in Spanish. Pronounced quickly, it’s very close to the Lebanese (perhaps other dialects too) equivalent of Bon Appetit.

Notwithstanding these parallels, the languages remain extraordinarily different. Communication with the fisherman was easier in French than it would have been with me speaking Arabic, but our exchanges remained elementary. Through gringo-style noun-adjective-unconjugated verb juxtapositions we understood that he had been living and working in France.

“Combien de temps ça fait que vous êtes là?” We asked, thinking it must have been a recent thing – that he hadn’t yet had the chance to really pick up the language.

“Onze ans,” our friend replied.

He had been working eleven years in construction in France. His wife and children were back there now, and he had returned to Alexandria for a month to fish on the concrete blocks propping up the peninsula guarding the western side of Eastern Harbour.

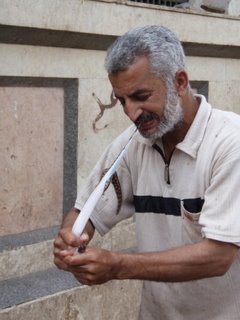

He told us he arrived every day midmorning and would leave around sunset. The only real difference between him and the other fisherman on the shoreline is that at the end of the day he ate his fish rather than selling them.

“Ils les vendent?” Without waiting for his reply I deployed the most well-oiled phrase in my underwhelming arsenal of Arabic:

“Bikam il kilu?”

“Ishreen Gineeh,” he replied. Twenty Egyptian pounds a kilo…that’s about four Canadian dollars.

The fish were tiny. I reckoned ungutted it would take 6-8 to make a kilo. Our friend had about 4 in his basket. It was four thirty in the afternoon. Maybe he’d lost his touch mixing concrete in la Banlieue Nord for eleven years, but even doubling his catch would have been a pretty meager day’s wage.

Four Canadian dollars can get you a lot around here, although I can’t say exactly how much, because I don’t know what the Eyptians themselves pay for most things. Let me give you an example.

The other day I had a fresh squeezed orange juice. There are little juice bars all over Cairo. They have large sacks of whatever fruit’s juice is on offer hanging at the entrance. The bars don’t generally have sitting room. Your juice is pressed your juice into a mug and you gulp it down at the counter, pay, and leave. In one and half seconds the mug is rinsed and ready for the next client.

My Aseer burtuan kabeer (large orange juice) cost me four pounds. As usual, I didn’t have exact change, which is a fatal error in Egypt (the worst is with taxi drivers). Somehow they never have change and you end up having to pay five times the price. In this case, however, it lead to an interesting discovery.

The owner opened his till and pulled out about three one-pound notes. For the rest, he had to give me 50 piastre notes (half-pounds), of which he had a wad as thick as Das Kapital. Five pounds says the most expensive juice in that shop was one pound.

An Egyptian, however, can get some mileage out of twenty pounds. Of course, the fishermen have to subtract overhead. Leaving aside the capital investment in the fishing equipment, daily operating costs are mostly of two kinds: bait and tea.

Bait is bought in the morning. It consists of little shrimps caught in nets by other fisherman. Thread a bare, barbed hook through the body of one of the little shrimps and you won’t need anything like the fancy blue fox and pixie lures we pay five dollars for in Canada. A day’s supply might cost a few pounds.

Tea you buy throughout the day. It is impossible for Egyptian men to talk, sit, and fish – that is, to live – without tea. I imagined that perhaps out on the peninsula they would be forced into forbearance. Our friend’s hospitality wouldn’t have it.

He insisted that we have tea. I objected. It might require walking back into town and therefore take a very long time. However, realizing – difficult though it is when accustomed to a certain lifestyle – that in that moment there was no more productive thing I ought to be doing, I accepted.

A silver platter with hot water, sugar and half a dozen glasses was almost instantaneously conjured – there, where we sat, on the peninsula.

Here, the glass is normally filled about one quarter full of sugar before tea is poured. In an effort to avoid returning to Canada a diabetic, my second most ready phrase is “min gheer sukkar,” or, “without sugar.”

You have to keep this phrase well-polished and ready to be drawn and fired any moment, otherwise your tea will be made up and thrust into your hands, after which it would be impolite to protest. I’m so quick Annie Oakley would be proud of me; my tea never has sugar.

We took our tea mostly in silence. I say silence though waves were crashing around us. Silence – in the sense of the opposite of noise – is not the absence of all sound, but the absence of human sound. Nature has her sounds – some of them deafening – but these are not noise.

The forced silence was good, for we speak too much and think too little. I thought of something I had once read about the British concept of friendship – that it consisted of knowing when to leave others alone. I look forward to this over the next two years in England.

The forced silence was good, for we speak too much and think too little. I thought of something I had once read about the British concept of friendship – that it consisted of knowing when to leave others alone. I look forward to this over the next two years in England.Away from the constant noise of Cairo, my mind began to wander. Place me next to the most crushing waterfall, or in the midst of the fiercest electric storm: this is not noise. They clear my mind, wash my soul, quicken my pulse and tighten my sinews. Tight like a strung re-curve bow or an exploding spinnaker flown in heavy winds.

When I see soft, bulging comfort I feel something is missing from it. It fails to inspire me. In its ease, its essence remains unrealized. Some things are made to be pulled taught and to bear forces. It may wear on them, but it is better than preserving them below their dignity.

But I fear more the anger of others in this discovery than I regret my sadness in witnessing it, so I leave be. My sadness is a double-sadness – first at the sight of things wasted, and second (perhaps a more profound sadness) at their innocence in not knowing this about themselves.

But I fear more the anger of others in this discovery than I regret my sadness in witnessing it, so I leave be. My sadness is a double-sadness – first at the sight of things wasted, and second (perhaps a more profound sadness) at their innocence in not knowing this about themselves.The fisherman spoke of how hard he worked in France. He worked eleven months of the year so that for one month he could come back to where he was from. Was that one month made so much better by being able to eat rather than sell his fish that it was worth giving up the other eleven? If he worked in Alexandria eleven months of the year, he probably could not afford to go fishing in France for one month a year, but I wondered if he would mind.

Did he go to France to dream for eleven months of returning to the place he had left? Fulfillment is surely more satisfying after deprivation, but I suspected the real reason was a combination of being able to fee like he “made it” in some way, and the desire to provide his children with opportunities and make a better life.

Did he go to France to dream for eleven months of returning to the place he had left? Fulfillment is surely more satisfying after deprivation, but I suspected the real reason was a combination of being able to fee like he “made it” in some way, and the desire to provide his children with opportunities and make a better life.A small-town boy goes to the big city to muck out a life. Making it consists of that moment when he returns home a prince and spins tales for family and friends about marvelous things only he understands. Only he doesn’t understand them – they are too big – and he doesn’t control them – they control him.

When he comes back to show everyone just how big he made it, he can say what he wants: no one else knows the truth. It’s a marvelous show, although sometimes it can be ruined – say by a father’s visit to the city. In Cry the Beloved Country even the father, on the path to revealing the fraud, cannot resist romanticizing and aggrandizing his existence when the chance comes: on the train to Johannesburg he pretends to have made the trip many times, when in fact it is his first. It’s so alluringly easy to appear sophisticated in the eyes of the unsophisticated.

I wondered how much better – and how much freer – the lives of the fisherman’s children might be in France than in Egypt. Often, the further from the centre the stronger one’s attachment to it.

The most fervently Catholic countries are furthest from Rome. In Europe one thinks of Poland and Spain more than France, Switzerland or Italy itself. Parts of Africa, most of Latin America and the Philippines are in a league of their own. Or, to take a an example from the Middle East, many of the feuds and allegiances at the base of the Lebanese civil war are stronger today in Ottawa and Montreal than in Beirut.

Like Lt. Hiroo Onoda, the outposts have kept the conflict alive long after it perished at home. And the suggestion that it has died (in Onoda’s case, in the form of pamphlets air-dropped by the US military) serves only to strengthen the resolve, and redouble the will to resist – as if to single-handedly prove its untruth.

For a Muslim family living in France, the feeling of isolation and the sense of loss of culture and language may paradoxically strengthen these traditions. The elders in particular may try to circle the wagons as they feel increasingly cut off from their own children and grand-children with whom they are unable to relate, or even to communicate.

The process is inexorable, but full of hemorrhaging. A generation – or a few generations – may be sacrificed along the way. Rarely, I think, would one find that a person genuinely desires to cease to be like themselves and to become like others. Yet that is the only thing that might avoid the upheaval.

There was only one woman among the fishermen. I caught her holding her child in one arm, and her husband’s fishing pole in the other. I stared at her and time imploded on itself, history was short-circuited and a momentary electric arc spanned a gap of millennia, followed by aching silence. Was this her child, or one of the lost sheep of Israel? And the rod a fishing pole or Moses’ scepter?

There was only one woman among the fishermen. I caught her holding her child in one arm, and her husband’s fishing pole in the other. I stared at her and time imploded on itself, history was short-circuited and a momentary electric arc spanned a gap of millennia, followed by aching silence. Was this her child, or one of the lost sheep of Israel? And the rod a fishing pole or Moses’ scepter?The silence faded and I awoke from my reverie, which had almost caused me to miss this moment. I quickly switched my brand-new digital camera to video-capture mode so as not to miss the miracle. When after about fifteen minutes the waters had not yet parted, I decided to move on. There were still so many museums to see and souvenirs to buy!

3 Comments:

you my friend... are too verbose.

i'll read it when the war's over hehe

Fink!

Verbose would be using too many words when fewer would be more effective, writing much and saying little or nothing. This is not Kiki!

Kiki's choice and use of words is craftsmanship that enriches the world, quite the opposite of verbosity, which spoils the experience.

In fact, Kiki describes life better than I believe most would experience it if they were there in Kiki's shoes. This is because Kiki has a gift for participation, observation and writing which are individually rare in others and which collectively is a unique gift Kiki possesses.

Kiki is magnificent in the choice and use of words. This is precisely what makes this description so powerful, so truly special, as is seen in all of Kiki's writings. Using less words would not create the pictures and convey the messages which Kiki does so uniquely, so beautifully, and so effectively.

This writing is art in words. Kiki's artistic talent with words is a talent more rare than artistry in any other form.

Kiki, you are just the opposite of verbose! Instead, you use just the perfect number of words. Critically important, what sets you apart from the vast majority of writers who are just ordinary, many of whom could be accused of being "verbose", is the way you magnificently craft those words which you so cleverly choose, in to the clear, vivid, and touching pictures you create in the minds of your readers. You create word pictures for your readers as if they were there seeing what you see, experiencing what you experience.

Don't be silenced by critics Kiki, if anything you should write more, share more, thus adding more to the pleasure and enlightenment of your readers.

You are one of the world's most gifted writers Kiki. To write less would be to deprive the world of your true creativity and special gift. To write less would be a tragedy and a real loss for your fellow man. To use fewer words would be saying little or nothing in too many words. And that would be verbose!

Write more, not less; share more, not less; may your verbosity rule.

Write on Kiki!

Hey! I found your blog courtesy of an aunt and thought I'd say hello. Your writing is quite vivid and I enjoyed reading about your experience with the world of war. What you learn from this and bring to your career and life in general is amazing! I'd love to hear from you, my email's the_dragon_sisters@hotmail.com.

Love,

your cousin Felicia

Post a Comment

<< Home